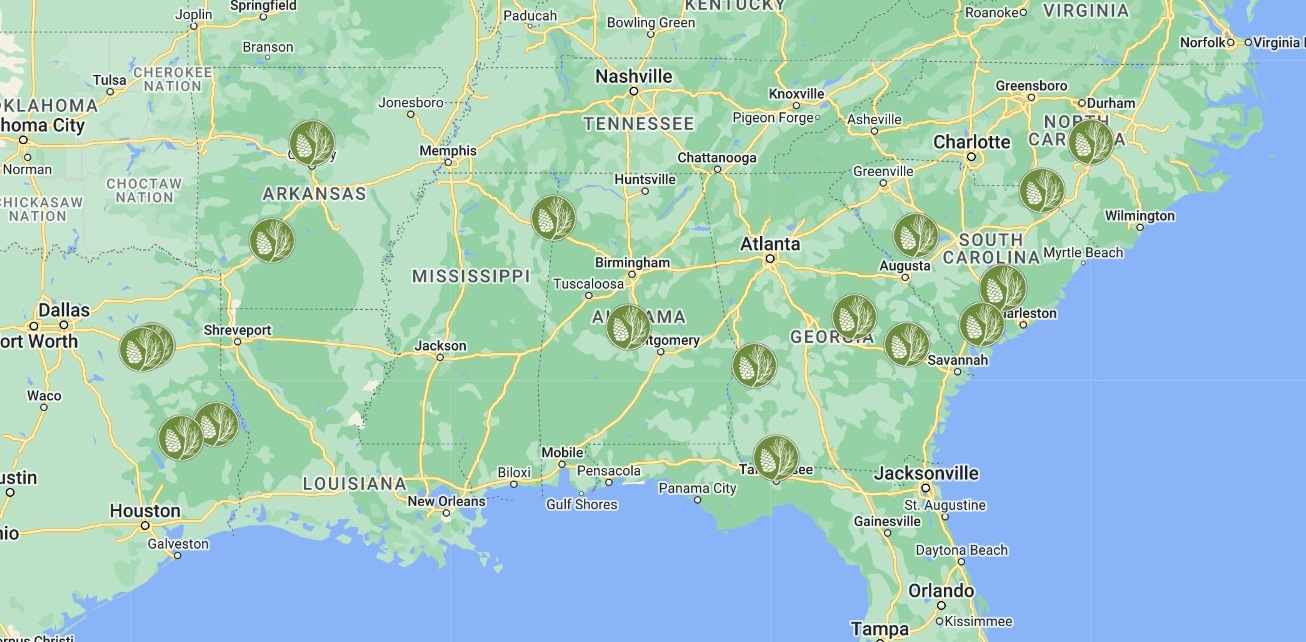

Authored by Blake Sherry

Blake Sherry is the Reforestation Advisor for Florida, Southern Georgia, and Southern Alabama.

Blake has been a valuable member of the ArborGen team since September 2024. Before joining ArborGen, Blake was a Procurement Forester for over five years.

Ask a logger, consulting forester, and a mill procurement buyer what a “bad” site is, and you’ll likely get three different answers.

A consulting forester might say a bad site is one with a low site index—meaning the site’s ability to grow trees productively is limited by factors like nutrient availability, soil texture, or moisture. A logger, on the other hand, will probably give a different answer: a bad site is one that’s far from a paved road, with multiple water crossings and long hauls from the woods to the loading deck. A mill buyer would most likely say a bad site is one where the wood can’t be accessed when the mill needs it—like during prolonged rain events.

Notice how two of the three definitions have nothing to do with the site’s ability to grow trees, and instead focus on the accessibility of the wood. Why wouldn’t the logger and buyer care primarily about the quality of the logs on the site? Because the logger will adjust his rate (to a degree) based on how productive he expects to be on the tract. Up to a certain point, what the wood looks like isn’t his first concern. When the soil is saturated and roads are washed out, the most important thing is simply finding a tract that can be worked.

For the mill buyer, accessibility is also a top priority. They’d rather purchase a tract with “fair enough” logs on a dry hill in January than “perfect” logs in a floodplain that can’t be logged when needed. That floodplain may have a much higher site index than the dry hill, but the best price per ton will be realized on the so-called “bad” site that can actually be harvested.

Excerpt from financial analysis of seedling categories across different site indexes by ArborGen Forest Planning and Analysis Manager Dr. Rafael De La Torre.

Contact your Reforestation Advisor for more detailed analysis.

In my short time working as a Reforestation Advisor, I’ve often heard the phrase, “put your best trees on your best sites,” with “best sites” referring to those with the highest site indexes. But those aren’t necessarily the most accessible sites—or the ones that fetch the best prices when mills are in need. A more productive tree will always provide more value, regardless of where it’s planted, compared to a less productive one. So ask yourself: Would you rather have your best trees—the fastest-growing, straightest, most disease-resistant—on an inaccessible “good” site, or on your “bad” site with well-drained soils and solid road access when the mill calls?